“It’s like how when you’re underwater, you can hear muffled noises or see people moving their lips, but you don’t actually know what they’re saying,” senior Maxine Olson said.

Deaf and hard of hearing students largely require interpreter services to understand and digest their classwork. Outnumbering interpreters at ten to two, deaf students at McNeil are left in classes without interpreters on a daily basis, often being without effective communication for multiple periods out of the day.

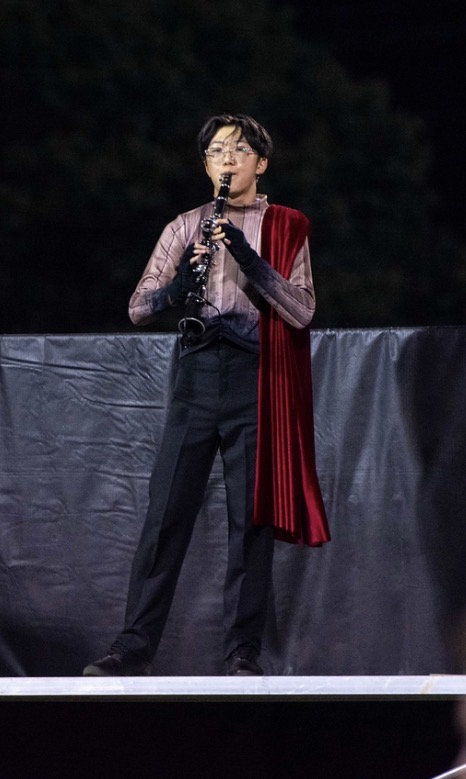

“If there’s no interpreters, then I’m stuck and I don’t know what to do,” junior Isaac Macario-Cipriano said. “I [try] to look around and figure it out, but then I have to write back and forth with the teacher [to understand]. If I have an interpreter, then the communication is just smooth.”

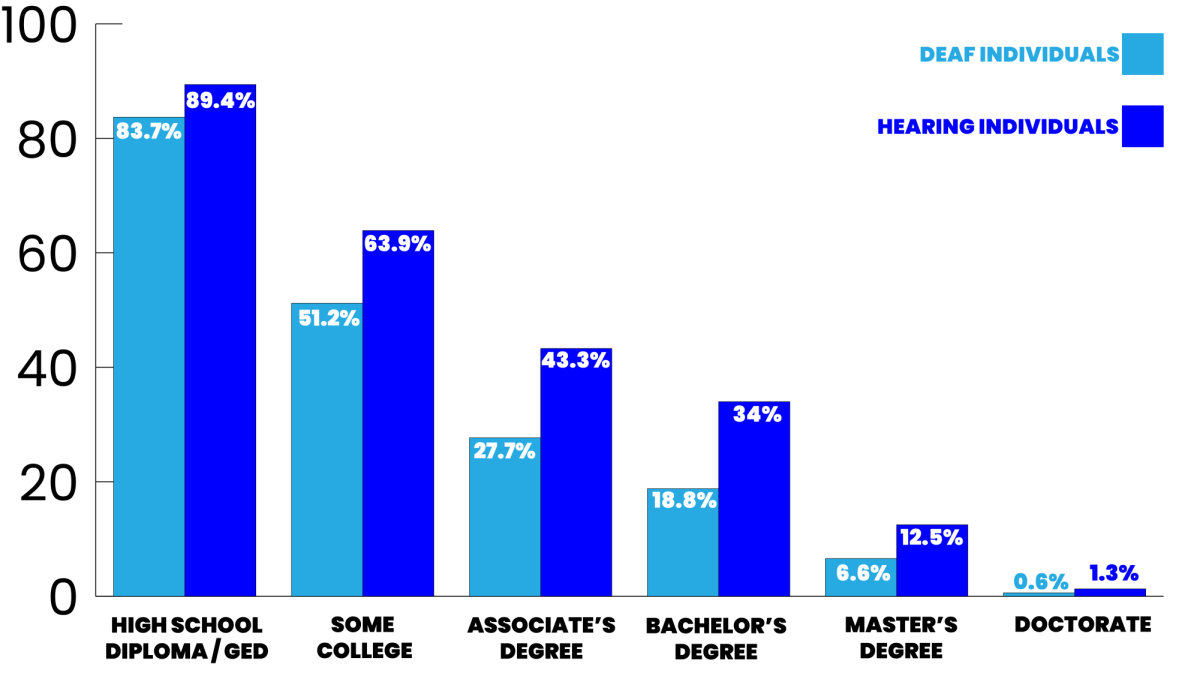

According to the National Deaf Center, only 83.7% of deaf people complete high school, compared to the 89.4% of hearing individuals. Additionally, only around 51% of deaf people go to and complete some college, with 63.7% of hearing individuals doing so.

“Deaf kids are more likely to have a lower education than hearing people, but it’s not because we’re more stupid,” Maxine said. “It’s because our education is being taken away, we need those interpreters to have a fair education like hearing kids.”

Deaf parent Jon Eric Olson grew up in school without hearing aids or interpreters, being forced to “fill in the blanks” of everything that wasn’t visual.

“I was lacking all the time,” Olson said. “When I was a little boy in school, when people would talk to me, I would be like ‘I can’t understand you’ and they’d get mad at me. I refused to ever ask anyone for help again, I’d just nod at everyone without knowing what they were saying just so they could be happy. I would miss a lot and I was barely understanding anything.”

Olson worries about how the shortage will affect his daughter’s education.

“I don’t want Maxy to go through it like me, I went through terrible experiences,” Olson said. “I want Maxy to have better access to interpreters and make sure she has better knowledge than I do. I was behind in education and I have terrible English. I wish I knew more.”

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), put into law in 1990, requires covered entities such as schools to provide effective communication from certified interpreters, with volunteers or companions of the deaf individual not to be used unless there is an immediate threat or under the request of a non-minor deaf individual.

“I don’t know if it’s because we’ve gotten away from the law [because] it’s been a long time, but it seems to be not taken so seriously,” deaf education teacher Brit Budd said. “Deaf and hard of hearing people are capable people who can be out in the workforce and helping and doing great things, but if we don’t provide them the same things that hearing people can also have, then they won’t ever have the opportunity.”

Budd has had to step in to interpret for students struggling in their classes, but the only problem is, she isn’t a certified interpreter.

“The con is it is not something I am skilled at, and it is not something that I feel confident at,” Budd said. “The pro is that I can be there for my kids, I can help them with things, and I can communicate well enough that I can get the message across.”

Budd interprets in two periods on both A and B days, yet interpreting for classes causes Budd to miss out on work for deaf education.

“As a teacher [and] deaf ed case manager, we have fires that come up and we have to put out,” Budd said. “Because we’re interpreting the class, we then have to leave, and so then [students are] left without an interpreter, or we can’t go solve the fire because we’re interpreting, and then the fire gets worse.”

Not only has she missed out on the social responsibilities of being a deaf education teacher, but the educational responsibilities as well.

“We lost an interpreter [weeks ago] because she went to another district to where she was offered more income, and due to that, it increased the need for interpreters for a specific class period,” Budd said. “That was a class period where I taught my own history class in my own classroom, and I had to rework the schedule to get rid of that class and combine it with another class period so that I could be available in seventh period to interpret.”

Budd and interpreter Valerie Rogers believe the shortage is primarily caused by the low salary being offered for interpreters in Round Rock ISD (RRISD).

“Most of it is the pay, because people will start here, and then they’ll get jobs in other districts because they pay more,” Rogers said. “We’ve been fighting for years to get a pay raise, and I think if that happens, more people would be willing to stay and not want to leave. “

RRISD interpreters asked the district for a pay raise for years, yet only received one years ago, not accounting for the soon to come economic boom of Austin.“Evidently it’s still not enough, because people are comparing our pay to other school districts,” Rogers said. “Because the cost of living is so high here, you’d think that they would match it. But everyone that’s worked here as an interpreter always had to have a roommate, they couldn’t make it on their own.”

Deaf education allocates interpreters into classes where they are “most needed,” for students that may be without any hearing aids or significantly struggle with certain subjects.

“It’s not fair that some of them have to go without an interpreter just because they have some hearing,” Rogers said. “Even though they have hearing, they still look to us, they still rely on us when they miss something. They’re not getting the services that they were required to have, it’s not fair for them.”

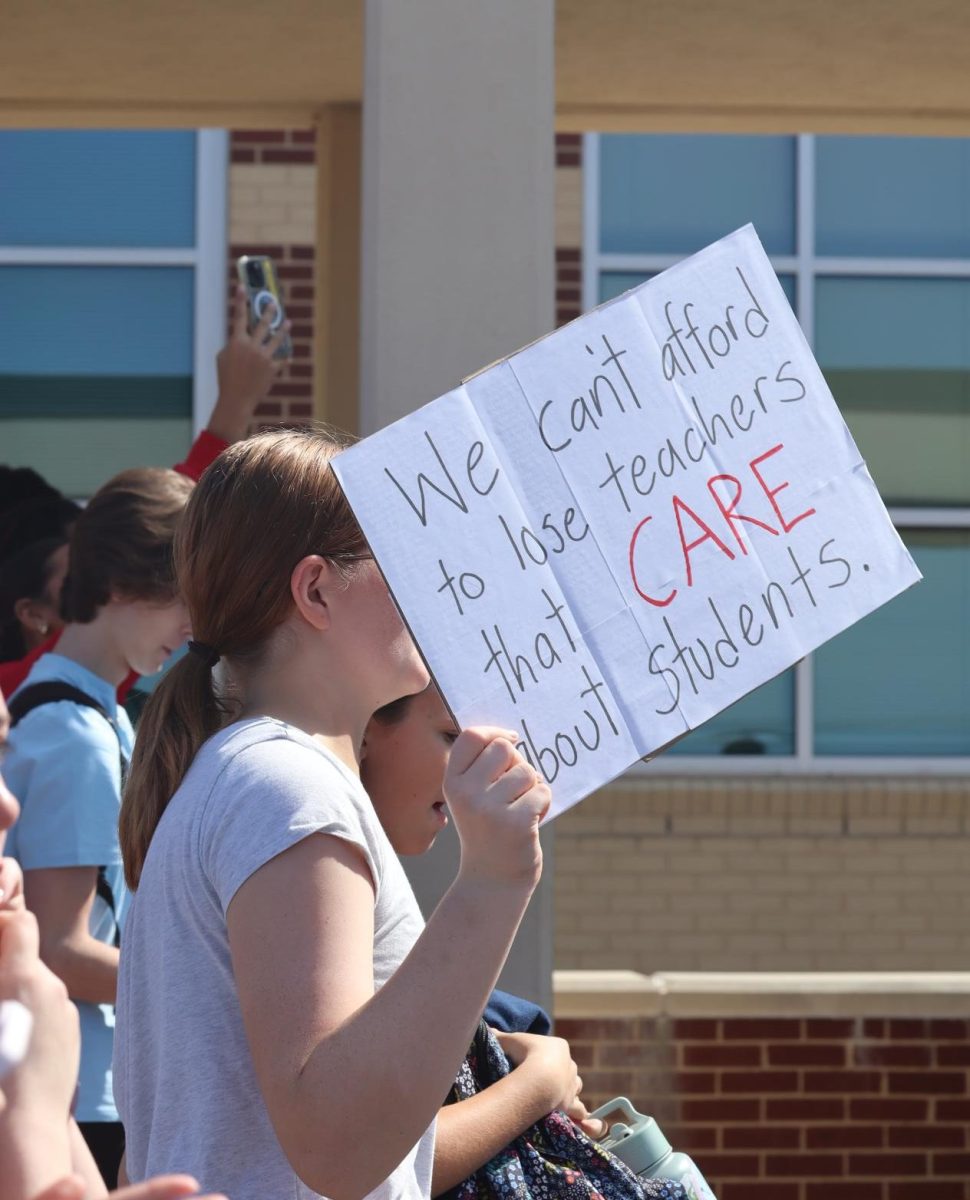

Without consistent, well-paid interpreters, deaf students feel a step behind hearing students in academics, having to put in more effort to close the gaps of what they missed.

“I kind of have to force myself to ask the teachers or ask my peers for help,” Maxine said. “That definitely helped, but I just feel like I shouldn’t have to do that just because I don’t have an interpreter. It would just be so much easier if I did.”

Instead of providing effective communication, the responsibility of understanding the material they missed is placed entirely on deaf students.

“I feel like I’m freeloading off of other people if I have no communication,” senior Sean Ervin said. “I don’t want that. It’s not fair [because] if I put in an effort to understand, I will also expect [hearing people] to put in an effort to understand.”

But for most hearing students, it’s effortless. While hearing students can often talk to their classmates or play on their phones while the teacher instructs and still understand, deaf students either give their all to comprehend instructions, or give up.

“When I start to struggle I tend to do less work,” Ervin said. “But sometimes even if I put in an effort in communications there’s still things I don’t know.”

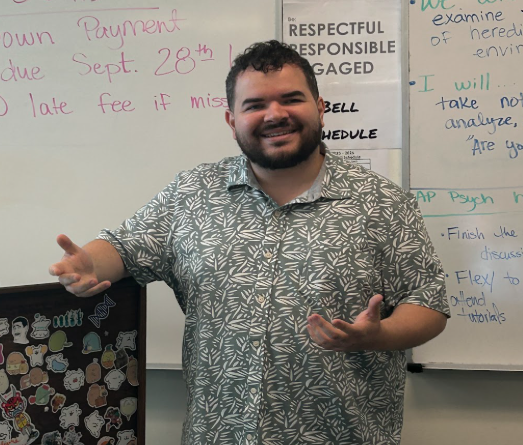

Human body systems and IPC teacher Lisa Flores believes that the relationship between the teacher, student and interpreter is essential for the student to learn.

“My relationship with the students can sometimes be a little bit challenging,” Flores said. “Sometimes students will not want to bother the teacher, so they ask the interpreter a question, who turns around and asks the teacher the question, and it takes twice as long to get information to each other. I know for me this year having the same interpreter, my students now feel more comfortable asking for help.”

Yet without interpreters for students to rely on, they’re forced to look to friends, classmates and family members to register the information they’re given.

“There’s a very high chance I might be their first deaf classmate,” Ervin said. “They don’t really know [how it feels] but they generally try to help me understand.”

Ervin and other deaf students primarily struggle with group work and situations where a room is louder or more fast-paced than usual, such as a socratic seminar.

“[During a socratic seminar] the whole time I was paying attention to the interpreter, so I never got a chance to raise my hand,” Ervin said. “I didn’t feel like I had a chance to really give my opinion.”

For after school events, students are often prevented from participating due to interpreters not being required unless a student makes a special request.

“I did feel not really involved,” Ervin said. “Socially, [I felt excluded]. If the team needed to work together, I would feel involved, everything else, no.”

When joining the wrestling team, Macario-Cipriano struggled to understand directions, only sometimes having an interpreter.

“I took my glasses off, and the interpreter was really far, and so it was really hard for me to kind of figure out what was going on,” Macario-Cipriano said. “I [felt] stuck and I can’t learn anything without them.”

Budd believes that the responsibility of making sure the presence of a school or outsourced interpreter should fall on the school, not the student as this may violate the ADA.

“You don’t put it on the deaf kid to have to do it, because that’s not equal access,” Budd said. “Hearing kids get to just show up to a meeting and they’re there and they have what they need. Deaf kids should be able to show up and have what they need and not have to think about the interpreter.”

Flores encourages the district to put in more effort to hire interpreters or find creative solutions to improve the quality of education for deaf students with the limited budget.

“I think if we can start investing in their support, we’re going to see greater, better results in the end,” Flores said. “It’s one thing to teach someone who speaks English already. It’s something else to teach a student that speaks and communicates in a different language, but those students need the support.”

The deaf education department continues to advocate for students, whether it means getting in touch with an interpreter or being a shoulder to lean on for them.

“We want to see them be successful in the world,” deaf education teacher Jennifer Downey said. “ It starts here to be the successful citizens that contribute to society, and if they’re unable to access education here, how can they [reach their goals]?”